Warming the species' last egg

Have you heard the story of the extinction of the Great Auk? We know exactly when their species was eradicated from the face of the earth.

Have you heard the story of the extinction of the Great Auk?

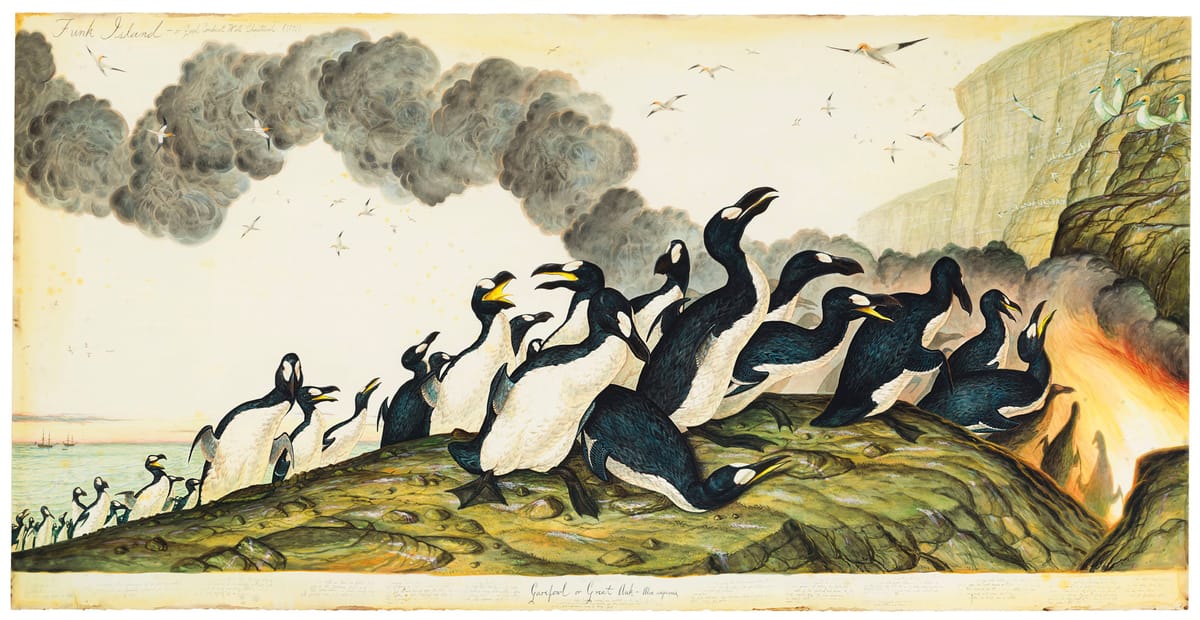

The Great Auk was an awkward, flightless bird which lived scattered across the northern Atlantic, and which gathered in large flocks to breed on barren islands off the coast of Newfoundland, Iceland, and Scotland.

With most creatures deemed to be extinct, we can't say for sure precisely when they became extinct. We might have the last confirmed sighting, and then that's it.

But in the case of the Great Auk, we know.

We know exactly when their species was eradicated from the face of the earth. And Beckett himself could not have written a darker or more absurd scene than this.

On June 3rd 1844, Jón Brandsson, Sigurður Ísleifsson, and Ketill Ketilsson scaled the rocky cliffs of the remote island Eldey, a barren monolith rising 70 feet over the surrounding ocean, off the southwest tip of Reykjanes Peninsula.

By 1835, this unforgiving stone had become home to the last breeding colony of the Great Auk, totaling only about 50 in number. Hunted at first for their down which was prized for making pillows, their increasing scarcity only made them more valuable in the eyes of wealthy collectors looking to own one of these rare birds.

By the time Brandsson, Ísleifsson, and Ketilsson arrived less than a decade later, only 2 Auks and their single egg were left on the island of Eldey. The Icelanders had been commissioned by a wealth merchant to acquire some exceedingly rare specimens.

In an interview with naturalist John Wolley, Sigurður gives us a detailed description of the events which followed the trio's arrival –

Jón Brandsson crept up with his arms open. The bird that Jón got went into a corner but [mine] was going to the edge of the cliff. It walked like a man ... but moved its feet quickly. [I] caught it close to the edge – a precipice many fathoms deep. Its wings lay close to the sides – not hanging out. I took him by the neck and he flapped his wings. He made no cry. I strangled him.

He made no cry. I strangled him.

They say that the Great Auk had no natural fear of humans.

They also say that Ketill Ketillson stepped on the last egg by accident.

Christ, have mercy.

Imagine for yourself being the last two of your species, brooding over and warming a little egg as you are whipped by the frigid wind of the North Atlantic. Like your parents before and their parents before them, you returned to this rock to carry out the task of perpetuating your lineage.

Now, you are the only two left. Huddling close, unsure about what comes next.

Was it a twisted mercy that these gentle creatures did not understand their situation? If they did, they would have come to the realization that the little one growing in this egg was condemned to suffer a fate worst than death.

This last Great Auk would have been forced to grow old in a world where no one would return their cry. As they closed their eyes one final time, all of the species' eons of history would slowly fade out into the cosmos – every grand migration and icy tribulation would receive one final curtain call in that bird's last breath.

But no, the Great Auk did not even receive an end we could call beautiful or poetic. Instead, they were strangled for money and stamped out by a misplaced human boot. Driven by the desire for comfortable pillows upon which to lay our heads, and consumed with the envious obsession of the collector, human beings drove the Great Auk to the brink of extinction, and then snuffed out the last fragile flame.

But still, even despite it all, I think that I would have kept warming that egg too, if I were a Great Auk. I would be found doing precisely what these two creatures were doing in diligently carrying out their task – keeping the child alive.

I also weep – I weep as I think of the thousands of small and callous decisions which brought the Great Auk to that place, backed into a corner on the island of Eldey. They were killed by men looking to make a quick buck, and were paid handsomely by a man of means who could think only of his own lurid curiosity.

After all, isn't that precisely how we humans might do away with ourselves too?