The Myth of Absolute Origin, or, watching Nisekoi with Nietzsche

I recently wrote a piece about the psychological trap which the childhood friend trope in anime represents for the protagonist (and the viewer!), but I want to keep exploring that line of inquiry by examining two other tropes which are intimately intertwined with the trope of the childhood friend -- "the childhood encounter” and "the childhood promise.”

Both of these tropes rely on a psychological mechanism which I call "the myth of absolute origin.” This absolute origin, ’Fate’ or ‘Destiny’ (unmei, 運命), provides us with a singular beginning in which we can find our meaning, nature, and trajectory. The beginning holds the key to the end, and even though we find ourselves in the middle of the story, we can’t escape the feeling that the end has been declared even before the beginning ever came about. That absolute singularity which synthesizes every element in our lives into a single unity in some primordial past provides us a firm ground to stand on. It comforts us in the midst of our questions and struggles, and we look back to it in hope as a clear sign for the future.

In anime, the “childhood encounter” trope often serves this function, and it plays out as follows — the main characters have a memory of sharing an experience with either their childhood friend or some unknown but sought after individual. This experience takes place when they are still small and impressionable, and it often entails either great beauty or some form of salvation from despair. Crucially, in this experience, one of them steps into the other’s life in a pivotal and unforeseen way which sets one or both of them on a new course.

In the case of the anime which I wrote on in my prior post (The Town Where You Live) the protagonist as a young boy happens upon the girl Eba alone and crying at a summer festival. In order to cheer her up, he takes her out to his favorite pond to watch the fireworks together. She is delighted and entranced, and they spend the rest of the evening laughing and playing together. Then they are separated, and don’t see each other again until they are in high school. The show urges us to accept that this primordial experience that they shared has bound their fates together, and that they are "meant for each other." In short, this singular event expresses the essence of their persons together, and as such defines the rest of their lives.

Jean-Francois Lyotard famously said that postmodernity declared the end of meta-narratives, but this is not precise enough. Postmodernity killed the idea of absolute origins, and only with the death of absolute origins did it bring an end to meta-narratives. Without absolute origins, a narrative can no longer be conceived of as an unfolding of a latent meaning present from the very beginning, but rather becomes a fundamentally open and contingent series of events in which each individual finds themselves responsible for their actions such that they have no recourse to any "fate" to justify their decisions for them.

We see this death of absolute origins clearly in Nietzsche’s work. His method of “genealogy” takes everyday concepts that we functionally treat as fixed entities, and he then attempts to historically trace their origin and development. He tries to get us to see that many of our concepts don’t even function today the way they originally did. But we’ve lost that understanding, and so we treat ideas as though they sprang into existence fully formed, and have meant the same thing in all times and places.

By doing this he does not purport to take us back to a pure origin from which we can recover the true meaning of a concept. He's not trying to say that we've forgotten what something really means, but rather, he's pointing out the fundamental plasticity of even the most elementary concepts. He does think that an origin can illuminate new possibilities and also reveal the stratagems of those who have re-valued and re-deployed concepts throughout history. But, he really wants us to learn that we can do the exact same thing with concepts today. Once you realize that concepts aren’t fixed entities, you can begin to re-shape them for your purposes.

The point can never be to enact an absolute recovery of a concept’s origin, because that would be to miss the point of origins. Origins are always contextual events that happen because someone chose for them to happen. This means that you too should adopt the stance of being a valuer and a chooser who builds tools and causes events in the world, but without falling back on a notion of fate or inevitability to either comfort yourself in failure or justify yourself in triump.

Origins are further problematized when we consider that the reasons people act are always motivated and shaped by values and practices that they themselves inherited and did not create. We can see how each “origin” has its roots in a plethora of other “origins” each which are themselves motivated, contextual, and also rooted in previous “origins.”

But surely the regression ends somewhere, right?

In order to begin addressing that question, I want to look at an anime that subverts the childhood encounter trope in revealing ways. In this anime, we see how the absolute origin doesn’t actually seal our fate, but actually we can change it based on who we’ve become since that event. In short, our choice is already included in the story, and thus the story can never be sealed from the beginning.

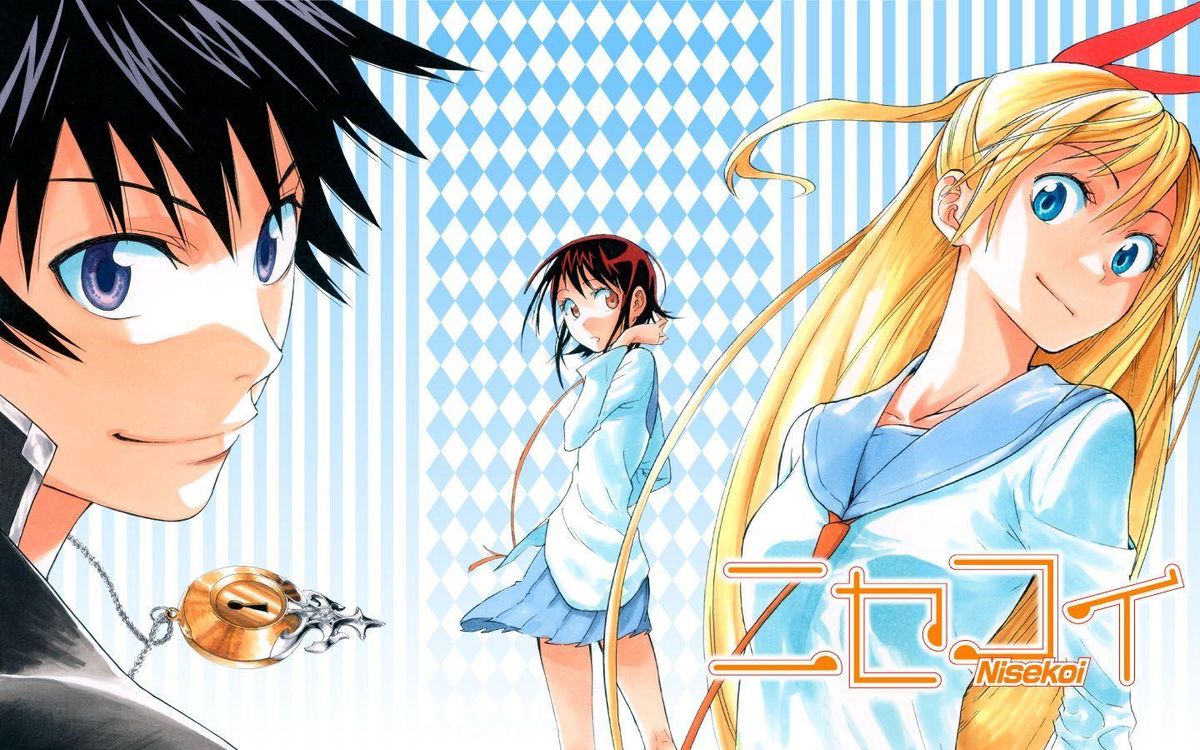

Nisekoi is infamous in the anime community for at least two reasons.

First, few anime have precipitated more vicious and entrenched “waifu wars.” With its large cast of female characters all vying for the main character’s attention, you’ll find eleven opinions for every ten fans when you ask about who “best girl” in Nisekoi is. And the anime didn’t even adapt the full manga, so there are even more female characters added later that anime viewers never get to meet.

Second, relating to this first point, Nisekoi was a long-running manga that had a failed adaption, despite being animated by a highly original studio with a rabid fanbase. Studio Shaft is infamous in its own right for its avant-garde and artsy style, which employs odd angles, quick cuts, surrealism, vibrant colors, extended dialogue, and call backs to the studio’s own original tropes (“the backward head flip”). After a successful first season, the second season experienced funding and popularity issues, causing it ultimately to be aborted half way through. The studio has never picked it up again, much to fan’s chagrin. Most believe it will never be adapted, largely because the manga has already finished its completion. It’s a truism in the anime community that an anime only exists to sell more manga, and that logic seems to hold in the case of Nisekoi.

The real point comes next.

Nisekoi subverts the “childhood promise” trope in important ways.

While the childhood promise trope is a distinct phenomenon from the childhood encounter trope, they essentially function the same way. In the childhood promise trope, the main character discovers that when he (almost always it’s a he) was a young child he made a promise to a girl that they would get married when they grew up. Such stories usually revolve around a memory or an object attached to the memory, and the driving force of the plot is the main character’s efforts to discover the identity of the girl he promised to marry. This trope too functions as an “absolute origin,” because it promises some ultimate answer to the meaning of all one’s strivings. It holds out the promise of a “right answer” to the choice of whom to love, and thus offers rest from the endless anxiety of whether one made the “right decision.” The absolute origin of the promise provides a fixed meaning to the flux of life.

In Nisekoi, the main character Raku Ichijo is the son of a yakuza boss, and the plot begins with his father betrothing him to Chitoge, the daughter of another yakuza boss in the area in order to create peace between their two families. There are three problems with this arrangement, (1) Raku and Chitoge hate each other, (2) Raku has a crush on a girl named Onodera, and (3) Raku has a necklace which he received from a girl whom he promised to marry when they grew up. This mysterious girl out there somewhere has the lock that can unlock the necklace.

Onodera and Chitoge offer one the best examples of the “childhood friend” vs. “new girl” trope in anime. Onodera is your quiet, demure, shy girl, who is kind, intelligent, and caring. She also is in love with Raku, but he has no idea, and she has always been unable to muster the courage to tell him. In the anime, she represents the classically “Japanese girl,” with jet black hair and a lack of personal confidence. Chitoge on the other hand is outgoing, brash, violent, can’t take social cues, and not the smartest. She represents the “hafu American” girl with blonde hair and complete disregard for social niceties.

-- Spoilers in the following couple paragraphs --

As the manga comes to a close (because you have to read the manga to get the end of the story), we begin to discover that many of the girls in the story were all there on that fateful day that Raku made his promise to that girl, all in unexpected and comical ways. After this discovery, it finally comes to light that it was Onodera who gave him the necklace, and that he had made the promise to her. She had the key all along.

However, and here is where the story diverges from typical “childhood promise” stories, Raku has already fallen deeply in love with Chitoge at this point. He has reached the point where he doesn’t feel constrained anymore by this promise that he made as a child. It no longer provides the secret meaning of his life, nor the security he once sought. Through developing his relationship with Chitoge, he has seen himself grow, become stronger, more responsible, and more the person that he wants to become, and Chitoge herself has grown by leaps and bounds as well.

In a classic anime move, right before the end of the story Chitoge leaves Raku for an extended period of time in order to work for her mom in NYC. She does this to test herself and grow herself in order to “be able to properly stand by Raku’s side.” Raku and Chitoge’s relationship caused them to want to become better versions of themselves, and also taught them how to sacrifice for another person. This was real life, unlike the fantastical necklace that Raku had always clung to for meaning, and the crush on Onodera that he had never been able to properly voice or act on.

In this subversion of the “childhood promise” trope, we witness Raku letting go of everything that the necklace, the key, and the promise had come to represent in his life, and to embrace the dynamic reality of love.

In many ways, this maps onto the childhood friend trope cleanly. The necklace and Onodera both are functionally the “childhood” friend, providing some minimal consistency and meaning to the overall narrative of his life, but ultimately serving to keep him trapped in the same patterns of idealism and failure. The introduction of Chitoge into his life violently upsets the smooth continual iteration of the same old cycles, introducing this new challenge and new possibility. Just like how brash and off-putting Chitoge is initially, so too the initial moments of having our world turned upside elicit a strong negative reaction from us. We perceive this foreign body as a threat, and so we attempt to destroy it. However, as Chitoge comes to understand Raku through the way he treats her with dutiful care and hopeful attempts at friendship, she begins to fall in love with him. She begins to change, and her heart is softened so that she begins to want to sacrifice for him and communicate her affection to him

Personally, I’m searching for an anime that expertly handles the “aftermath” of the protagonist leaving the childhood friend behind. Onodera really draws the short stick in this anime. She “loses” not because of anything ultimately wrong with her, but because she continually delays telling him about her feelings, and doesn’t have the confidence to challenge Raku to grow, ultimtaely she misses out on him. Chitoge “wins” because she becomes the catalyst for change in Raku's life, something that Onodera never was for him.

But, I mean, did the final chapter of the manga really have to show Onodera baking the cake for Raku and Chitoge’s wedding? I say this to point out that Onodera deserves a love story too, and she doesn’t get one. The childhood friend who “loses” needs a love story where they get to meet someone who can help them move on, and not just move on, but leave that old story behind by showing them how to write a new story.

But I digress.

In Nisekoi, Raku overcomes the myth of the absolute origin through realizing that love is about finding someone real who you can build something together with, not about fulfilling some primordial longing to find “the one.” This “one” is not a fated individual who will come along to save you out of your life, but is the individual who you discover in the midst of life’s struggles, and who becomes your companion right where you’re at. By breaking from the myth of the absolute origin, one becomes radically open to our freedom (and attendant responsibility!) as a subject which can choose and change.

But, you might ask, how does this fit with Nietzsche's Eternal Return?

We will leave that for another time, friend.