This essay continues our series on the emergence of self-destructive behaviors.

Suicide and Fantasy

In 1962, 44% of the people who killed themselves in England and Wales used the same method — inhaling the "town gas" flowing freely in the pipes inside their homes.

This gas was a noxious mixture of chemicals, and would never pass current standards of what humans should be exposed to on a daily basis.

Case in point — you could reliably kill yourself by breathing it for an extended period of time.

But beginning in 1965, England overhauled its entire gas infrastructure to transport natural gas instead of town gas. It was an enormous undertaking, and the transformation was gradual, so the project didn't see completion until 1977.

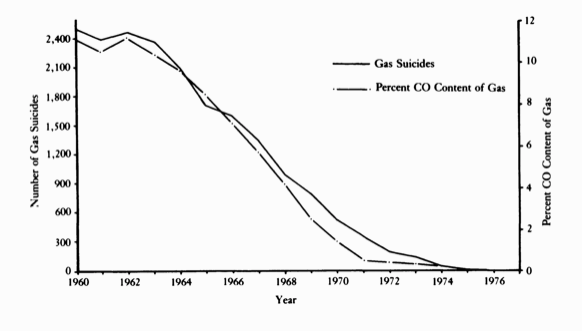

Naturally, as town gas was removed from homes, suicides by town gas decreased — eventually disappearing altogether.

Folk wisdom regarding suicide typically suggests that if regulation eliminates one method of killing one's self, those who want to kill themselves will simply find another way to do so.

In his book Talking with Strangers, Malcolm Gladwell refers to this line of thinking as 'displacement.' The same logic of displacement often appears in public policy discussions concerning, for example, putting up preventative measures around San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge in order to prevent suicide by jumping.

Despite the outward plausibility of the idea of displacement, Gladwell points out that the data on suicide doesn't support it.

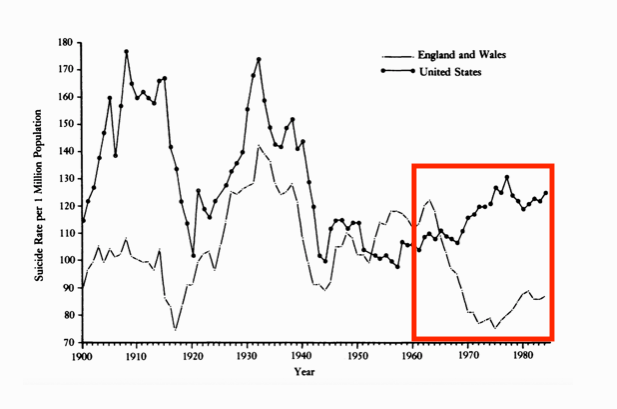

See the graph below which visualizes the absolute suicide rate per 1 million individuals in England and Wales versus the United States during the period when the UK was transitioning from town gas to natural gas.

This chart shows that as the availability of town gas decreased, fewer people overall were killing themselves in England and Wales.

In other words, people who would have killed themselves with town gas were not availing themselves of other methods. They were choosing to live instead.

Gladwell argues that the concept of 'coupling' explains the data better than 'displacement' does.

Coupling, as its name suggests, describes the strong correlation between two phenomena. If we change one of the variables, it has a statistically significant effect on the other. The co-presence and interaction of the two variables produces a more accurate and predictive picture of the outcomes we might be analyzing.

In the case of the correlation between the decrease in the availability of town gas and the absolute decrease in suicides, Gladwell suggests that the two phenomena being coupled are suicide and fantasy.

Town gas was a crucial prop in how people staged the fantasy of their own death, and with this crucial prop now absent from their repertoire, their fantasies had to adjust accordingly, some even foregoing the fantasy of suicide altogether.

Why not simply claim that the lack of opportunity was to blame? The simple phrase "lack of opportunity" conceals the mechanisms operating under the hood. After all, you cannot kill yourself without a plan.

If suicide is murder, then you have to plot murder before you can carry it out (Karl Menninger's Man against Himself). You must be seeking an opportunity, envisioning how you will carry out this act.

Here in the process of suicidal ideation we find ourselves in the realm of fantasy.

Plath's Fantasies

To demonstrate his point, Gladwell embarks on a detour through the life of a famous writer who killed herself with town gas — Sylvia Plath.

On February 11, 1963, Plath stopped up the gaps under the door in her kitchen, turned on the gas, and shoved her head as far into the oven as she possibly could manage.

This wasn't the first time that she had attempted to kill herself, but more importantly, this wasn't the first time that she had imagined killing herself.

Consider this section from "A Birthday Present" written near the end of 1962, in which Plath imagines breathing clouds of carbon monoxide (a central ingredient of town gas) --

“But my god, the clouds are like cotton.

Armies of them. They are carbon monoxide.

Sweetly, sweetly I breathe in,

Filling my veins with invisibles…”

Gladwell also points out a passage in the Bell Jar in which the protagonist Esther Greenwood toys with the idea of suicide, first asking a boy on the beach, Cal --

"Cal seemed pleased. “I’ve often thought of that. I’d blow my brains out with a gun.” I was disappointed. It was just like a man to do it with a gun. A fat chance I had of laying my hands on a gun. And even if I did, I wouldn’t have a clue as to what part of me to shoot at.”

She then talks about her failed attempt that morning to kill herself by strangulation with a silk cord – she kept aborting the attempt when she started to feel flush. She then attempts to drown herself while she is swimming with Cal --

“I dived and dived again, and each time popped up like a cork.

The gray rock mocked me, bobbing on the water easy as a lifebuoy.

I knew when I was beaten.

I turned back.”

Gladwell brings this section to a fine point – "Plath’s protagonist wasn’t looking to kill herself. She was looking for a way to kill herself.”

And this requires the exercise of imagination.

Notice also the divergence between male fantasy and female fantasy. Cal imagines himself blowing his own brains out, and Esther scoffs at this as a typical male way of thinking.

She's not wrong! It's fascinating to note the differences in the ways that men and women actually do commit suicide.

The most common way for men to commit suicide is by firearm, which also has the highest success rate of any of the most common methods (82.5%), but women tend to opt for experimenting with the much less successful methods such as pills (1.5%), cutting (1.2%), drugs/poison (1.5%), or gas (41.5%).

In fact, it was female suicides which dropped much more dramatically than male suicides when town gas began to be phased out.

Why?

Gladwell lets the poet, Plath-admirer, and suicide victim Anne Sexton tell us --

“'I’m so fascinated with Sylvia [Plath]’s death: the idea of dying perfect,' she told her therapist. She felt Plath had chosen an even better “woman’s way.” She had gone out as “a Sleeping Beauty,” immaculate even in death. Sexton needed suicide to be painless and leave her unmarked.”

Just like Plath, Sexton also chose the riskier method of gas (lower likelihood of success), but which had the benefit of preserving her beauty in death.

The male method of suicide with a gun brutally instantiates the direct desire to completely destroy and efface the self, but the seemingly female coded fantasy of the "immaculate death" seems to speak to a desire to be and yet still desired by the other, almost as though she finally manages to steal back her enjoyment by unexpectedly and irreversibly taking away the other's object of desire.

That last point bears some future investigation, but we will forego that now to simply conclude by bringing this piece back to its original assertion – self-destructive behaviors require an imaginative or fantastical component for them to function, that is, the creature must be able to relate to a self which is grounded primarily in the visual realm.

Here, I believe, lies a fruitful line of investigation.

Thanks to Malcolm Gladwell for his excellent book Talking with Strangers. This essay presents and builds on chapter 10 of that book.

To read the next essay in this series, click here.