Oedipus in a Biopolitical World (Part 3)

Thus – while the glory of Oedipus the King has passed, I propose that we should hail the appearance of a new and different king – the prophet Job.

This is the final installment in a three part-series. In the first part, I talk about "the compulsion to speak" in our biopolitical society. The second part elaborates Foucault's concept of biopolitics and biopower. Today's piece finally begins to answer the question of what role psychoanalysis can have for us today.

This piece opens with a short reflection on hope. I think this re-characterization of hope as a form of negativity (not just a "positivity" or "optimism") illuminates the spirit of what I'm trying to do in this series and my work as a whole.

Prologue – An Inconsolable Hope

What is more inconsolable than hope?

The one who refuses satisfaction — they are like a god.

The one who hopes steadfastly waits for the appearance of their hope, refusing any substitute or counterfeit which the world might proffer them.

Who can manipulate such a one?

Nothing that another can give could satisfy them. They are unswerving, moving heaven and earth simply by virtue of planting their feet fast in one spot.

When everything else moves, they stand still.

“I would prefer not to," they intone, as the world's tumult rages.

Who can reason with the hopeful one? They cannot be talked off the ledge. They cannot be persuaded to turn aside to the paltry prizes of man.

Brothers and sisters, become utterly inconsolable. Weave your web, and sit down in the center, waiting with all your being for a heavenly meal to finds its way into your maw.

Accept no substitute. Believe no man’s honeyed words. Live with eyes open wide, looking at the invisible horizon.

As you sail the interior ocean, only hope's obstinacy can sustain you in those dark and cloudless nights. That co-pilot will lead you to the far shore.

Many have stopped short, and many have lost themselves in the detours. They have received their reward.

But here we stand — we shall not be moved, we shall not be satisfied, and we trust no promises of man. Who can control such ones?

The hopeful one is free. They shall receive their reward.

The return of the Negative

Byung-Chul Han in his book The Burnout Society describes our biopolitical situation as one defined by an excess of positivity. His work echoes Foucault's critique of Freud by arguing that the idea of repression no longer provides a useful explanatory lens for understanding the pathologies which today proliferate in our society.

Anxiety, depression, addiction, eating disorders, self-harm – these symptoms which present themselves among us at an alarming rate all bear witness to a people struggling to find limits in a world without them. We can feel ourselves being absorbed into the circuits which compose the global network of people and capital, its machinic substrate.

Psychoanalyst Diego Buriol notes something similar to Han's observation in his own clinical practice, observing how patients today are more willing than ever to freely speak about their feelings, but that they experience no attachment to these desires as their own. They are like passive observers in their own minds, watching as the inner and outer world pass them by, totally alienated from their subjectivity, driven forward by what feels like alien forces inhabiting their bodies.

This then seems to be the need of our time – to recover the practice and power of negation. How does one intervene in the smooth functioning of the machine? How does one introduce a cut in the tissue of life or a division in the fabric of reality? From whence come limits, and how can negativity set us free?

Psychoanalysis stands apart from the scientific and medicalized discourse of our biopolitical society by its maintaining the necessity of negativity for the increase of life and the freedom of the subject. Thus, it finds itself uniquely positioned to speak to these conundrums, but it must do so with an understanding that our strange situation has shifted. Old ideas must be applied in new contexts, for the old answers will no longer suffice.

The Inconsolable Hope of Job

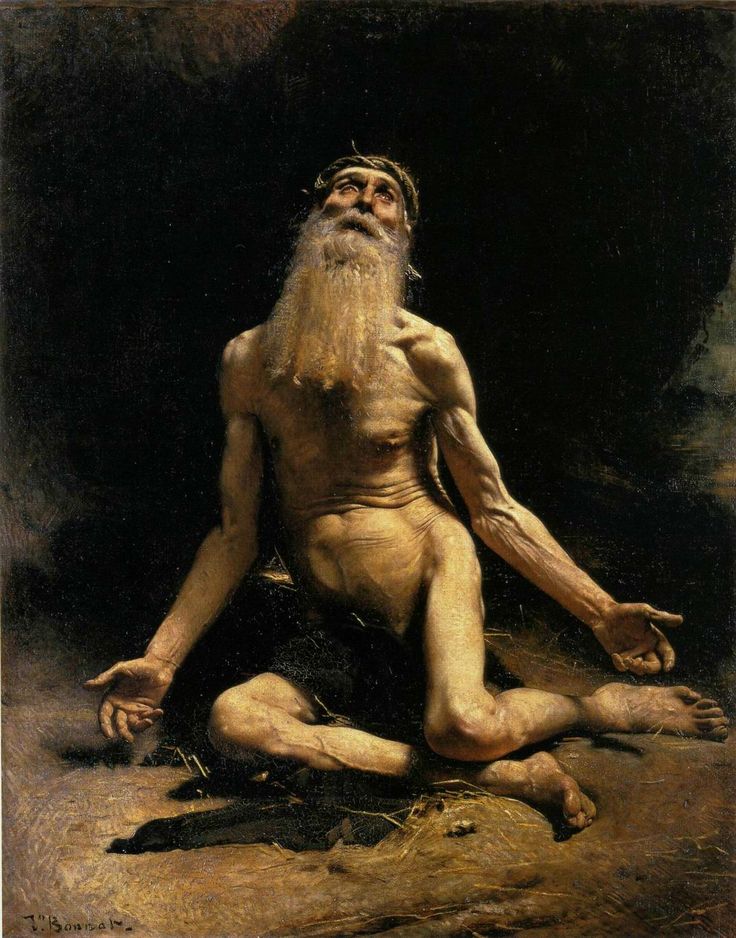

Thus – while the glory of Oedipus the King has passed, I propose that we should hail the appearance of a new and different king – the prophet Job.

He who sat in ashes and who cut himself with a potsherd, and yet who steadfastly refused his friends' urging to curse his God, this figure of negativity confronts us with the challenge of living in a divergent way from our biopolitical society.

Having lost his children and his wealth, his health and his vitality, and even his own wife having turned on him, Job nonetheless was animated by a hope which refused any sort of human consolation. He sat immovable in the dust.

25 For I know that my Redeemer lives,

and at the last he will stand upon the earth.

26 And after my skin has been thus destroyed,

yet in my flesh I shall see God,

27 whom I shall see for myself,

and my eyes shall behold, and not another.

My heart faints within me!

Job 19:25-27

This hope became a form of negativity which resisted the optimizing and rationalizing explanations of the people around him.

His friends theorized that the suffering he was undergoing must be some form of punishment from God for sin, but Job refuses to rationalize his situation in that way. He knows the character of God, and he will not repent of his righteousness, and thus he waits patiently for God vindicate him from him humble estate. He knew that this humiliation would not be his final end, but also that it was not in his own power to transcend this situation.

We can understand this hope of Job as an attachment to something higher than the world of mechanical relations of utility or the karmic economy of spiritual reward and retribution. Instead, through this attachment which flows into his seemingly useless behavior of resisting his friends' explanations, Job testifies about another possibility for living, one which moves beyond the realm of Law into walking with God in love.

Psychoanalysis does not resist this essential human tendency to organize our lives around worship. In fact, it asks precisely about the central form of waste – for what is worship but a pouring out in waste? – which forms the core of our subjectivity. At the heart of every human is a void, something which cannot be totalized, and a void which resists the smooth functioning of the machine.

Lacan says that we humans are like cameras which are jammed. We are the sand in the gears of the cosmos, and so we play and laugh and enjoy our excessive existence.

The one who is jammed, resists.

The one who resists, hopes.

The one who hopes, worships.

The one who worships, is free.