An animal born too soon must make masks

We feel that we cannot relate to ourselves until we have performed the necessary alienation of objectifying ourselves, thus producing an object we take to be ourselves.

We feel that we cannot relate to ourselves until we have performed the necessary alienation of objectifying ourselves, thus producing an object we take to be ourselves.

Jacques Lacan attributed the source of humanity’s foibles to our young being born too early in their process of natal development – human babies experience what is colloquially referred to as a "fourth trimester." During the first three months of the infant's life outside the womb, they nonetheless remain both biologically and psychologically in utero.

Our young are odd in this respect, especially when compared to other mammals. You'll watch a foal take their first steps within an hour of being born, but a human baby can't bear being physically separated from their mother, much less handle the mundane biological operations most of us take for granted, such as moving gas through our intestines or regulating our internal temperature.

I bring this up because I think we're liable to underestimate the formative role this 'being born too soon' plays in the development of human subjectivity.

In particular, I'm left asking the question of how the infant's experience of such a profound impotence indelibly marks us as human beings.

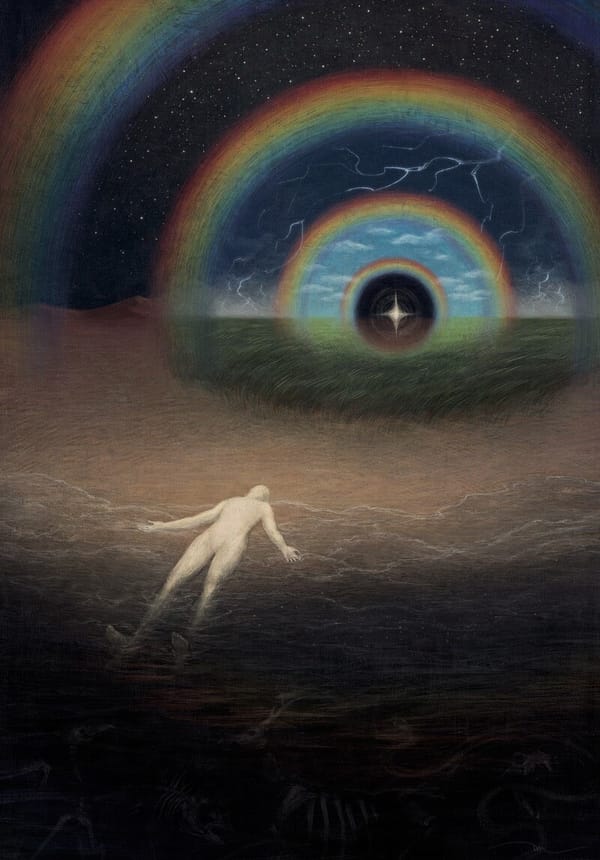

In this respect, I'm struck by how many of consciousness' mechanisms of control seem to trace their root back to this original experience of the chaotic cloud of partial drives which the infant helplessly experiences. They undergo these horrors as having have been cast out of Paradise, the all-sufficient Womb, desperately washed ashore in this harsh world, with only an imperfect caretaker to cling to.

What sort of creatures would this make us? A single word rings in my mind –

- "Clinging" -

Jean Piaget famously observed that at around 7-8 months infants develop what we now call 'object permanence.' Object permanence is simply the notion that even if I can't see an object right at this moment, it still exists. As a developed human being, you probably take for granted the mental construct that the car parked in your garage right now does not stop existing when you aren't looking at it. When you enter your garage later, the car is still going to be there, right where you left it (at least, we hope...).

However, the relationship of one to one's self doesn't seem to exhibit this same sort of permanence which we attribute to other objects. There is nowhere we have "left it," and thus nowhere for us to return to in order to "find it." The self is sporadic in its appearances. Rather, it comes and it goes, appearing and disappearing, always a little too late or a little too early. It seems not quite the same object every time it appears, and sometimes we don't even recognize what we're looking at when it does appear. We lack this carefully delimited substance which we can point to and say "that's me, "that's what I am." Every time we attempt to do that, it slithers away from us. Whenever we push on it, it scuttles away, just out of reach.

Nonetheless, humans do manage to attribute object permanence to our selves. We believe that our self is “still there” even if we're not focusing on that focal point in our consciousness which we take to be "me." Even though we don't necessarily know where to "find" our self, we take it as a given that we're still "there."

So, how does the self acquire this object permanence?

There is a clue in the name of the phenomenon itself — object permanence. In order for the self to be chronologically durable, it has to become an object.

In On Narcissism, Freud says that “a unity comparable to the ego cannot exist in the individual from the start; the ego has to be developed.“ [77] We come to experience the self as having object permanence when we make of ourselves an object. This unified object which we call the self coalesces into a mental object, for it has no physical reality. It inhabits only our psychic realm. However, much like a magic talisman, this psychic object nonetheless facilitates a relationship between the ideality of conscious experience and the materiality of the body. We feel that we cannot relate to ourselves until we have performed the necessary alienation of objectifying ourselves, thus producing an object we take to be ourselves.

Here I think we find the beginnings of the human obsession with the visual field which we began to probe in last week's piece. We humans intuit in the image that which we take ourselves to lack — a unity from which flows all manner of other desirable properties, such as coherence, legibility, and durability.

The unity of the image especially contrasts sharply with our earliest experiences of our body. The child finds their own experience to be a chaos of drives, swellings, urges, needs, and demands. It's chaotic and scary. Think of the child who starts crying after suddenly jolting awake. They were terrified by an uncontrollable force in their body rousing them against their will. Further, the child even lacks the mobility and motor skills to flee threats or find necessary sustenance. The infant can only lie on its back as waves of powerful drives wash over its helpless little body, throwing its fragmented and disjointed consciousness into disarray.

The child thus experiences their body as a dis-unity, something it cannot fully control. From the start, humans feel like strangers in our own house.

I think that objects provide — or, more important, lure us with the offer of — what we sense that we lack. When a child sees an object, they see something which doesn't lack the way they do. The image presented to the human eye enjoys a static quality and structural coherence which everything about my experience of myself seems to be lacking. Objects have this durability that we just don't have as humans. While this engenders an anxiety about what we lack, the mechanism which emerges to manage this anxiety takes the form of an "object envy."

In The Lacanian Subject, Bruce Fink says, “Now the ego, according to Lacan, arises as a crystallization or sedimentation of ideal images, tantamount to a fixed, reified object with which a child learns to identify, which a child learns to identify with him or herself.” [36]

In short, the ego is an object. But, not just any object – an image specifically.

One of Lacan’s most famous theoretical proposals was “the mirror stage,” and the mirror stage describes precisely this process of the child seeing and identifying with images. As the child looks into a surface which reflects back an image, they begin to form an attachment to this image as “them.” This is me, intuits the child. In the scene of the mirror stage, the mother or father might even be present, reinforcing this impression explicitly (”Look, sweetie! That’s you! Say hi!”).

The ego-images the child identifies with are ideal in the sense that they do not possess the pain and instability which characterizes our experience of our body from day one. Over time, we collect myriads of these ideal images, through such varied activities as observing others, hearing stories, reading books, and watching movies, and so on. The ego is formed as these (often incongruent) sequences of images coalesce around the hardened core of our perceived lack, an anxiety about what we might be missing. They enthrall us with a perfection that far exceeds our own, and in an effort to lend coherence to ourselves, we identify with these images.

But, why pay so much attention to the ego?

In my own thinking, I see at stake in all this the question of agency. Who, or rather, what is the agent within consciousness? What is acting?

The operation which employs the ego in consciousness strengthens the erroneous impression that it is the ego which acts when we act, and, unfortunately, contemporary psychological discourse has mostly contented itself with lending encouragement to this mistake. While the realm of the ego remains much touted nowadays as the realm of freedom, the psychoanalytically-informed account I've begun developing here points at a more disturbing conclusion – identity dominates the realm of visual fixation, narcissistic attachment, ultimately results in an anti-vital reduction of the dynamic human person to a dead object.

As the human being identifies with their ego, attributing their actions to their ego, they fall prey to the trap of identity. The irony is that the living being has fastened themselves to an inanimate corpse with no power of its own, always parasitic on the subject, but nonetheless claiming responsibility for every victory and failure. The patient has bound themselves to their ego, and they give it power by feeding it. We do this, because we believe we are feeding ourselves. But the ego is a parasite which will eat you alive.