When the Pope anathematized the teachings of St. Augustine

How did the crypto-Catholic Jacques Lacan give us the Calvinist Slavoj Žižek? And could St. Augustine's theology be the key?

In honor of Reformation Day, I'm happy to share an essay combining some strange bits of church history with some speculations about Lacan, Žižek, and Augustine.

Did the Roman Catholic Church anathematize the teachings of St. Augustine?

It certainly looks like it.

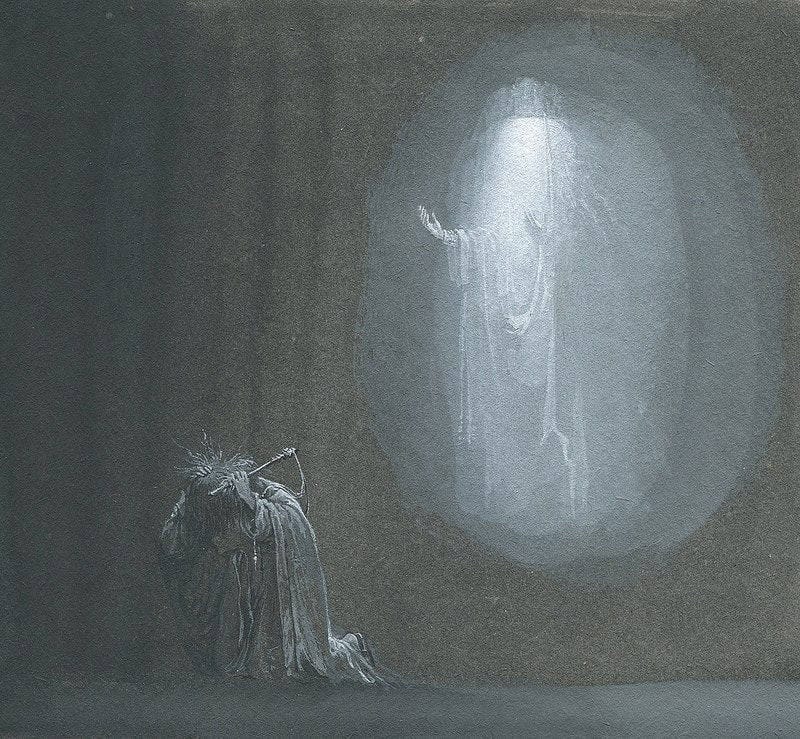

In 1653, Pope Innocent X promulgated the papal bull Cum Occasione which condemned five propositions attributed to a French Catholic sect referred to as the Jansenists. However, these five propositions were almost certainly the unadulterated teaching of St. Augustine who the Jansenists claimed as the spiritual and theological authority of their teachings.

The Jansenists bore the name of one Cornelius Jansen (1585-1638), often referred to by the Latin Jansenius, who was a professor of theology at the University of Leuven, and who had written the multi-volume work Augustinus in which he propounded with great detail and with extensive quotations the teachings of St. Augustine on predestination, divine grace, and free will.

The posthumous publication of this immense work of scholarship unwittingly sparked a theological movement in 17th century France which rose up to oppose the dominant Jesuit faction who the Jansenists accused of teaching a semi-Pelagianism in which the human will cooperates with God's divine grace unto salvation.

Despite their protests to the contrary, these Jansenists were virtually Calvinist in their theology (if not their ecclesiology), teaching that human beings were totally depraved and unable to attain salvation on their own. For humans to have faith, God must provide His spirit to work even the will to have faith, and that only God can work faith in us. Further, God bestows this effectual grace according to an eternal plan of predestination determining who He will save.

The most famous proponent of Jansenism turned out to be Blaise Pascal, that celebrated polymath and author of the Pensees, whose sister Jacqueline served as the prioress of the primary Jansenist monastery in France, Port-Royal. His famed Provincial Letters were his intervention into the ecclesiastical battles which were unfolding between the Jansenists and their Jesuit opponents.

The history and controversies surrounding the Jansenist movement are fascinating, and I highly recommend that you pick up Leszek Kolakowski's book God Owes Us Nothing: A Brief Remark on Pascal's Religion and on the Spirit of Jansenism to learn more about this heretical Roman Catholic movement which took up the mantle of St. Augustine, and which represents, in Kolakowski's reading, a decisive moment when the Roman Catholic Church opted for Aquinas and Modernism against Augustine and the pre-modern.

However, the rabbit hole continues to go deeper, because the relationship between the Jansenist movement and Blaise Pascal provides a crucial link in a question which has been bugging me – how did the crypto-Catholic figure Jacques Lacan give us the Calvinist Slavoj Žižek? (these are the things that keep me up at night!)

This self-professed "Christian Atheist" Slavoj Žižek has publicly said that if he were a Christian, he would be a Calvinist. Further, he also follows in the footsteps of Lutheran philosopher G. W. F. Hegel by taking up his mantle of defending a Protestant dialectics against the Catholic analogia entis or analogy of being (see his debate with the Anglo-Catholic theologian John Milbank in The Monstrosity of Christ, or check out my reflections on that book).

Despite Žižek's predilection for Protestantism, his philosophical predecessor Jacques Lacan seems to have been more heavily influenced by Catholicism, making cryptic remarks throughout his life about being the product of priests or prognosticating that the Catholic Church as the embodiment of true religion would eventually triumph. He also provides extended exposition at certain points in his lectures on Catholic figures such as Teresa of Avila and Blaise Pascal. Finally, his own brother Marc-Marie became a monk at the Benedictine abbey Hautecombe.

So, to reiterate the question, how was this Protestant Žižek born from the Catholic theorizing of Jacques Lacan? While the influence of Hegel cannot be ignored, it cannot be decisive, for many have interpreted Hegel from within the Platonic tradition in which Catholic theologians also find themselves laboring. There must be something within Lacan himself which can be taken in a Protestant direction, for Žižek claims that it was precisely reading Hegel through Lacan which revealed to him the idiosyncratic reading of Hegel which he propounds today.

As I found myself puzzling over this question, I serendipitously ran across this presentation from Dominic Hoens on the connection between Jansenism, Blaise Pascal, and Lacan's reading of Pascal's wager. At last, I had found the missing link!

Pascal professed doctrines like double predestination, irresistible grace, and original sin, all of which he argued were the clear teachings of St. Augustine. However, Hoens focuses on one particularly interesting and dividing question, namely, "does God ask the impossible of us?" When God commands us to believe and to have faith, does God demand something impossible? The Jansenist would argue that, yes, He does. Absent the grace which He may choose to give or not for no merit of our own, we cannot love God as He requires of us.

To my mind, this orienting question and its shocking answer drops us into a tragic view of the world which is at once both Augustinean and Lacanian.

I've written in the past about how Lacan sees human subjectivity as a product of our too-early birth and the bodily impotence which follows from "the fourth trimester." In Lacan, we encounter a vision of the human as crippled or disabled by freedom and subjectivity, a creature whose instincts are plastic and out of joint, assailed by fantastical images, and penetrated and supplemented by these symbols which we call language. Forced to exchange signs with other creatures in the desperate search for love, a nothingness which none of us have but which we all wish to give, and ultimately must find our enjoyment precisely in the failure of things to close or complete themselves.

Such a tragic vision of the world runs like a ley line from St. Augustine to Calvin and Jansenius, and finally re-appears under the strange guise of the psychoanalytic theory of Jacques Lacan and Slavoj Žižek, all while retaining its distinctively theological undertones.

This insight at present appears to me as little more than an overwhelming intuition, so I'm mostly groping after words to capture what exactly it is that I'm seeing. But, can you see what I'm seeing? I hope to explore this line of thought more, possibly through a series of recorded conversations or a collected anthology.

Augustine opens his Confessions by praying that "we are restless until we rest in you," but what sort of rest is available to finite creatures who participate in the divided and conflicted Absolute we encounter on the cross of Jesus Christ? Perhaps we are being confronted with an entirely different vision of existence, one which remains essentially tragic while nonetheless offering the possibility of rising up to some hitherto unforeseen glory.

Speaking of St. Augustine, a piece of mine appeared in Agony Magazine's 4th edition which released a couple months back on the feast of St. Augustine. That work stitched three of my posts together into a proposal for a new perspective on desire, with a lot of help from Lacan and a little bit of help from Augustine. Check out Agony Magazine and all the other great writers featured in their pages!